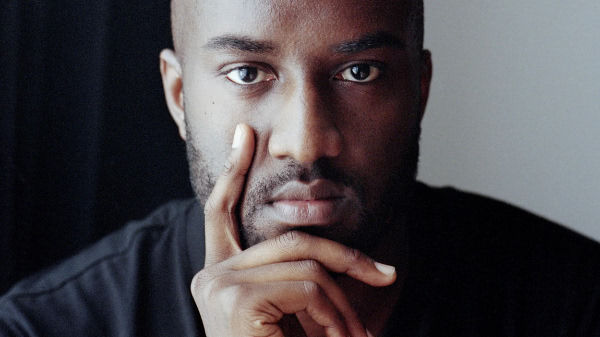

Virgil Abloh: The Designer of Progress

Luke Leitch, writing for Vogue:

Virgil Abloh … died [Sunday] aged 41, will be remembered as one of the most popular and influential fashion designers of his era. As both the founder of Off-White and the Creative Director of Menswear for Louis Vuitton, Abloh’s ascent from show-crashing fashion tourist in 2009 to the very apex of the global luxury industry at the time of his passing is arguably the defining fashion story of the 2010s. […]

Abloh’s influence, however, will also be remembered well beyond fashion. It was only six months ago that he observed in an interview: “I operate by my own rules, in my own logic, and I’m not fearful.” […]

Abloh’s greatest product of all was the varied creation of opportunity for others to whom opportunity is otherwise routinely denied. In 2017, for instance, he created a uniform for Melting Passes, a team of recently immigrated soccer players in Paris whose lack of residency status meant they were excluded from playing in official competition, and later included them in the audience at an Off-White show. There were 3,000 students at his first Louis Vuitton show at the Palais Royal gardens in 2018. He worked to support skateboarders and surfers in Ghana, the birth-country of his parents, and provided funds to fix park and play facilities in Chicago, the city he called home.

One Historic Black Neighborhood’s Stake in the Infrastructure Bill

Audra D. S. Burch, reporting for The New York Times:

In Tremé, century-old oak trees, towering and lush, once lined the wide median along North Claiborne Avenue. As far as the eye could see, they formed a protective green canopy above children playing after Sunday Mass, couples holding picnics and families celebrating the parades and pageantry of Mardi Gras.

“If you talk to anybody in Tremé, they can tell you about the day the trees came down or when the highway was built,” said Lynette Boutte, a hair salon owner whose family’s roots in the neighborhood extend back generations. She wants to see the highway, nicknamed “the bridge” or “the monster” by residents, closed and retrofitted as a green space.

“Monster” sounds right. The city dropped a monster right on top of the neighborhood.

For a long time, the avenue was bustling with work and play. It was lined with insurance businesses, hardware stores, pharmacies and tailors, along with jazz halls and social clubs. Much of that changed with the highway project, which was pitched as an efficient way to shuffle cars downtown and keep it thriving. About 500 homes were cleared to make room …, a disruption that led shops to shutter and property values to fall.

See also: Removing urban highways can improve neighborhoods blighted by decades of racist policies

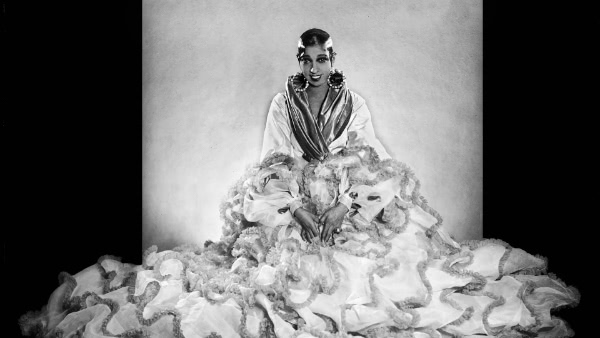

Josephine Baker is the first Black woman to be inducted into France’s Pantheon

This week, Baker was laid to rest alongside France’s most iconic national figures.

NPR’s Eleanor Beardsley reports on Baker’s extrordinary life for Morning Edition:

Born into a poor family in St. Lewis, Mo., Baker arrived in the French capital in 1925 to be part of an all-Black dance show. She was just 19 years old. […]

The little girl who had cleaned houses at the age of 9 in St. Louis became a star in Paris and part of the city’s intellectual and artistic elite of the 1930s. […]

Baker hid resistance fighters, Jewish refugees and guns in her chateau. She sang for French troops and undertook espionage missions, risking her life for her adopted country. Baker was awarded medals for her valor. And in 1961, she was decorated with the Legion of Honor medal. […]

In 1963, she addressed Martin Luther King’s March on Washington dressed in her French Resistance uniform, with medals across her breast.

Phillip Atiba Goff: How can communities reimagine their approach to public safety?

NPR’s TED Radio Hour:

Psychologist Phillip Atiba Goff analyzes data on how racial bias affects police behavior. He shares how communities can rethink their public safety systems, and ultimately better respond to crises.

The discussion focuses on Goff’s 2019 TED talk on racism and policing. Goff says solving the problem of racism begins with accurately defining what racism really is.

When you listen to the way we talk about trying to cure racism, you’ll hear it. “We need to stamp out hatred. We need to combat ignorance,” right? It’s hearts and minds. Now the only problem with that definition is that it’s completely wrong -- both scientifically and otherwise. One of the foundational insights of social psychology is that attitudes are very weak predictors of behaviors, but more importantly than that, no Black community has ever taken to the streets to demand that white people would love us more. Communities march to stop the killing, because racism is about behaviors, not feelings. And even when civil rights leaders like King and Fannie Lou Hamer used the language of love, the racism they fought, that was segregation and brutality. It’s actions over feelings. And every one of those leaders would agree, if a definition of racism makes it harder to see the injuries racism causes, that’s not just wrong. A definition that cares about the intentions of abusers more than the harms to the abused -- that definition of racism is racist.

But when we change the definition of racism from attitudes to behaviors, we transform that problem from impossible to solvable. Because you can measure behaviors. And when you can measure a problem, you can tap into one of the only universal rules of organizational success. You’ve got a problem or a goal, you measure it, you hold yourself accountable to that metric. So if every other organization measures success this way, why can’t we do that in policing?

Goff goes on to explain how his organization, the Center for Policing Equity, uses data to help police departments around the country reduce the level of force they use in the communities they serve.

See also: Reimagining police departments with safety and justice in mind

Michael B. Jordan on His Growing Empire, New Love and Seizing the Moment: “It’s My Turn”

Rebecca Sun profiles Jordan for The Hollywood Reporter:

As he toplines the romantic drama ‘A Journal for Jordan’ and prepares his directorial debut (‘Creed III’), the actor-producer discusses his “clean brand,” new willingness to share his personal life and the price of agitating for real change in Hollywood.

Inside Virgil Abloh’s Emotional Final Show For Louis Vuitton

Samuel Hine, writing for GQ:

As the finale wrapped, Abloh had one final message for the assembled: “There’s no limit,” he said over fading music. “Life is so short that you can’t waste even a day subscribing to what someone thinks you can do, versus knowing what you can do.” Where Abloh would normally take his bow, his Paris-based studio team, many in tears, walked together down the runway. Fireworks lit up the sky over the water, and when they fell silent many attendees remained in their seats. […]

After the show, the crowd slowly filtered past the statue [of Abloh] to the after-concert, held in a field back on land. Above the thousand-strong crowd, a drone light show spelled out “Virgil Was Here” in the sky.

The Louis Vuitton Spring/Summer 2022 Menswear show:

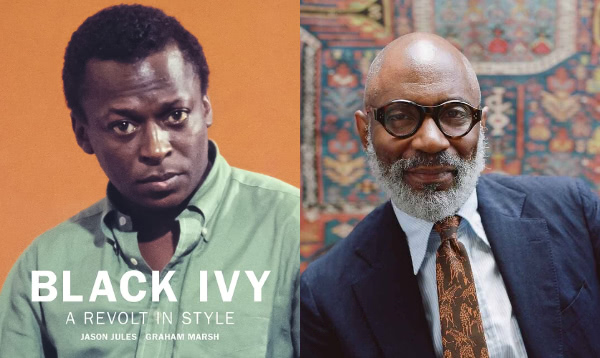

The Making of Black Ivy Style

The Times’ Guy Trebay speaks with Jason Jules about his new book, Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style:

In Mr. Jules’s telling, the adoption by generations of Black men of sartorial codes originating among a white Ivy League elite may initially have been a natural inflection point in the arc of men’s wear evolution. Yet it was also a conscious development, one with a strategic agenda that extended well beyond the obvious goal of looking good.

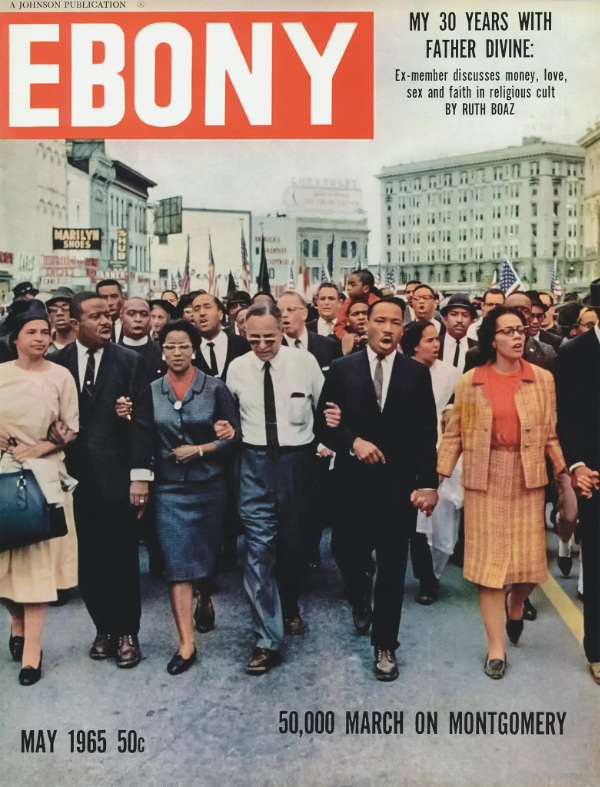

Jules says on whether civil rights activists of the ’60s adopted the Ivy style as part of a strategy:

If we recognize that Ivy style is the attire of a cultural or social elite and that people may have wanted to be seen as equal to anyone in the United States, then yes. It makes perfect sense to adopt that style. I am not suggesting anybody was so naïve as to believe that dressing it was being it. Still, you can see in this adoption of a very traditional uniform associated with, say, Harvard or Yale — a look steeped in heritage and history and that has these clear modernist connections — a strategy that might be attractive to activists.

Jules continues:

Of course, people wanted to look good. But the embrace of Ivy style had to do with a desire to be seen as equal and not to allow particular prejudices and barriers to prevent you from doing that. I think of it as being a little like dressing rockabilly to get into a rockabilly club. There was an implicit challenge too, of assumptions about who gets to own a certain style.

Jennifer Packer: Painting as an Exercise in Tenderness

Aruna D’Souza, reporting for the Times:

While painting her subjects, usually those closest to her, with a deep sensitivity, she allows them to stay just beyond our visual grasp. It’s an act of protectiveness and care that is moving and still leaves the viewer with much to contemplate.

The title of the exhibition, “The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing,” refers to a passage from Ecclesiastes that describes the human yearning for knowledge that can never be sated. It’s a paradoxical but entirely apt entry point for this painter, whose work is based on keen observation, while consistently probing the limits of representation.

Packer’s retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art runs through April 17, 2022.

Thanks for reading. See you next week.